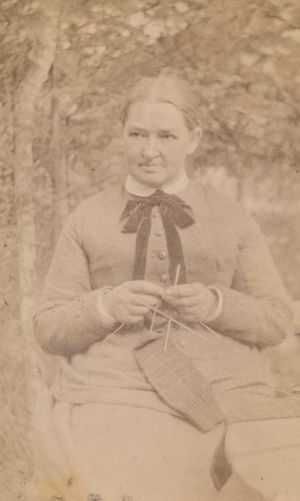

Minette Blaufuss (Da VII 4)

Minette Adeline Maximiliane Kunigunde Sofia Johanna Eckart, (*June 9, 1830, in Emskirchen, Germany, †January 25, 1901, in Brunnenreuth, Germany), married Konrad Blaufuss on October 28, 1852, in Emskirchen, Germany

Source Text Concerning Minette Blaufuss

Short biography about Minette, written down by her son Georg, from the Chronicle of the Eckart Family (FA-S346); compiled by Otto Eckart in 1927, part handwritten and part typed:

My mother was born on June 9, 1830, attended elementary school at the market town Emskirchen as did all her numerous siblings and was confirmed by the highly esteemed priest and later "Senior" (head priest) Cloetez. After leaving school, she at first stayed at home to help her mother with the inn. It was not long before she got acquainted with the school administrator Konrad Blaufuss, with whom she became betrothed as a 17-year-old girl and married five years later.

The Revolution of 1848 had unearthed the moral defects in the German people, so that Germany’s church circles, prompted by Heinrich Wichern from Hamburg, Candidate of Theology, and father of the Inner Mission, now tried to take action in order to help and heal. Based on Wichern’s model, the greatest care was taken with the neglected youth. In Riedenhausen in Lower Franconia, several clergymen and men interested in the church banded together to form an association on June 5, 1848, and decided to establish a salvation institution for neglected children. The Trautberg estate near Kastell, a farmstead owned by the Count of Kastell, was purchased and converted into an institution. The president of the association, the priest Walter von Rüdenhausen, managed to entice my father, who worked as a teacher in Schwabach at the time, to the post as housefather. After my father had left his good post as a teacher, he joined Wichern in his large reformatory institution in Hamburg, the "Rauhes Haus", for six months in order to prepare himself for the work. He took up his post as housefather and teacher on September 25, 1850. Two years later, he took his betrothed, who had prepared herself for the profession as housemother in the reformatory in Herrnprechtingen [he probably means Herbrechtingen], Württemberg, as his wife.

My father was everything in this institution: housefather, teacher, and manager of the estate. My mother was responsible for all the housekeeping and the girls’ education. They were assisted by several male and female helpers. It was a life full of toil and work, trouble and annoyance with these mostly quite depraved boys and girls. In addition, there was the constant worry about the means for maintaining the institution; since it was financed by voluntary contributions, one had to constantly knock on doors and beg for money. Most of the time, my father was also responsible for this task. As my parents were in the best years of their lives, they overcame these difficulties with ease.

It was at the Trautberg that most children were born, namely: Johanna, Elise, Babette, Maria, Georg and Hans.

As my father also committed himself to the matter of the socially lost as a writer, he soon became well-known far and wide, and his judgement was frequently sought when founding new charitable institutions of that kind. The association Johannisverein, which still performs its beneficent activity in the care of released prisoners to this day, established two institutions for such unfortunate people near Trautberg: one at the estate Mutschenhof for sons of better families, the other in Atzhausen, near Kleinlangheim, for members of the working class.

Differences of opinion with the administration of the Trautberg estate led my father to resign from his post as housefather and to take over the management of the Mutschenhof institution, of which he was already the inspector. Shortly after the war of 1866 – that is how far back my personal memories extend – we moved from Trautberg to Mutschenhof, approximately three kilometers away. This estate’s next neighbor was the mill Mutschenmühle, driven by the brook Grindleinsbach, which springs out of the ground near Kastell. The fact that the miller had to drive over the Mutschenhof grounds whenever he wanted to get to the road caused various disputes. Thus, there were new difficulties that had to be overcome by exercising patience and [illegible]: (1) the cramped housing conditions, (2) the unruliness of the pupils, (3) the hostilities of the miller, which were eventually settled in a trial. Again, the main burden, the very difficult housekeeping, was shouldered entirely by my mother. Father took care of the very extensive correspondence. He spent almost the whole day in his writing room. We children attended school in Rüdenhausen but did not learn much. Reading, writing, arithmetic, and catechism were the only subjects. In view of a better education for their children – with two more girls born at the Mutschenhof, Luise, who already died after a year, and Christine – my parents decided to move close to a town. However, this could not be carried out immediately. At the Mutschenhof, we were visited every year by dear relatives. Grandmother regularly came from Emskirchen. Uncle Johannes and beautiful Aunt Susanne called in, Uncle Christian from Honolulu spent some days with us, also Uncle Max before leaving for the Hawaiian Islands.

This is also where we witnessed the great events of 1870 in which my father took the liveliest interest. I still recall how my father once came home from Kleinlangheim, all hoarse. When my shocked mother asked him what the matter was with him, he said very quietly: "Napoleon is captured." And thus, he had shouted himself hoarse in his enthusiasm about the joyful event. A master of speeches, he had to make a speech at the peace celebration in Kleinlangheim. I still remember the first sentence: "I take my hat off to the German warrior!" It was a time of great enthusiasm and high hopes. I often heard my father state: "Our children will now have a better life." When remembering this great period, one’s heart aches, and, lamenting, one has to proclaim with the poet: "German people, you most glorious of all, your oak trees stand, you have fallen!"

The wish to move close to a town came true shortly after the peace agreement. He bought an estate in Neuried, near Munich, called "Neunerhof" and planned to establish a reformatory there. It was a farmstead with 40 Tagwerk of fields, a residential house, and a farm building, two horses, eight cows, poultry, hares, and all inventory in good condition. We arrived in Munich at the beginning of October, with the cheaper Oktoberfest train, and were met at the station by Uncle Schneider who took us to his apartment in the street Rumfordstrasse, where we all spent the night with our precautionary Aunt Jakobine. The next day, we first visited Uncle Fritz and Uncle Johannes, who lived close to each other at the time, and then went to Neuried. We spent a short happy time there. Everything was new to us, and the most pleasant thing was that the Catholic inhabitants of Neuried did not show the slightest fanaticism towards the Protestant newcomers, but even obliged us in a very neighborly way. My father followed a few weeks later, already ill. On the train, which was not heated at the time, he had caught a cold which developed into double pneumonia of which he died on December 4, 1871. He was buried by the Munich priest Wilhelm Rodde, who proved to be a good friend of the family once again.

Following father’s death, the real struggle for existence started for my mother, who was 42 years old at the time. Her situation was in no way enviable: an indebted estate, no widow’s pension, no money in cash, seven untrained children, the eighth was on the way, totally unknown neighbors. It was her unshakeable trust in God that sustained her in these times of serious distress. For her, it was certain that God can and must and will help; and he helped good people. Friends of father’s came and her capable siblings, Uncle Fritz and Uncle Johannes, supported her with words and helpful deeds. The Eckarts’ strong sense of family manifested itself in the most beautiful way in this situation. First of all, it was necessary to ensure the children’s education. Johanna, the eldest, could continue to attend Fernsemer’s institute in Krumbach; Elise the women’s school for practical work training; and Babette, who had already stayed with Uncle Johannes before the move, the art school; Maria was taken in by Uncle Schneider and still went to elementary school; Hans and I were admitted to the Protestant orphanage, which had been founded by Reverend Rodde, in the upper part of the street Gartenstrasse. It would be too much to describe in detail how this excellent woman fought for the education of her children; this would make a book of its own. Suffice it to say: she accomplished a matter dear to her heart, namely providing for all her children, before closing her eyes forever.

Johanna, who had worked as a teacher for several years, married the teacher Johann Fink, Elise, mother’s faithful support for many years, espoused Otto Schilling and Babette wed Ernst Luthardt, a civil servant for the government. Maria went to England and lived there as a nursery teacher for 22 years, almost always in the same family; Georg became a teacher in Munich; Hans a priest and later a professor of religion in Nuremberg; Max also a priest, now in Sünna (Thuringia); Tina married the post office clerk Hans Klein and now lives in Munich as a widow.

In 1887, mother sold the estate in Neuried, then lived in Planegg for a few years, then stayed alternately with Hans in Feldkirchen and Langenau, with Elise in Karlstein, near Reichenhall, with me after the death of my wife Augusta and eventually with the youngest, my brother Max, a curate in Brunnenreuth, near Ingolstadt. This is where she was able to spend her 70th birthday. It was probably her last joyful day. All her children had come as well as her siblings Fritz and Jette and Cousin Reuter. The speech that I gave in the name of the siblings expressed the childlike gratitude to such a courageous mother. Philipp Reuter, who had to participate in a military exercise in Ingolstadt at that time, came and took several photographs of the cheerful company.

In early January 1901, my mother started to experience breathing difficulties due to fatty degeneration of the heart; she passed away gently on January 25. We took her mortal remains to Neuried where she was buried alongside her husband on the 27th. It was a rough, stormy day. All the relatives from Munich and nearly all villagers appeared in the small graveyard. The itinerant preacher Wilhelm Rudel, now dean in Würzburg, held the funeral oration and blessed her.

Mit ihr ist eine tapfere, aufopferungsfähige und menschenfreundliche Frau dahingegangen. Ihr Wesenskern war unerschütterliches Gottvertrauen, das sie in allen Lebenslagen aufrecht erhielt u. ihr alle Schwierigkeiten zu überwinden half. Ihr erzieherischer Einfluß auf ihre Kinder, mündlich oder brieflich ausgeübt, war groß. Ihr allein – nicht der Schule, nicht der Kirche – verdanken ihre Kinder ihre moralische Bildung. Mehr als Werte wirkte ihr Beispiel. Für ihre Kinder scheute sie keine Opfer, keinen schweren Gang, keine sauere Bitte. Trotz aller trüben Erfahrungen, die ihr nicht erspart blieben, setzte sich in ihrem Herzen nicht wie so oft geschieht Menschenverachtung und Neid fest. Ihren Mitmenschen gegenüber war sie immer freundlich und hilfreich, sie freute sich mit den Fröhlichen und weinte mit den Betrübten. Ihr starker moralischer Sinn schärfte ihr das Auge für die Aufdeckung aller Heuchelei. Oft warnte sie den Vater vor falschen „Brüdern“, die mit dem Mantel der Frömmigkeit umgehängt, sich an ihn heranmachten u. hätte mein Vater den Rat seiner Frau immer befolgt, er hätte sich vor vielen Enttäuschungen bewahrt. Ihre Dankbarkeit gegen alle die, die ihr in der Zeit der Not geholfen hatten, war groß. Mit inniger Liebe hing sie an allen ihren Geschwistern. Durch einen ausgedehnten Briefwechsel blieb sie ihren Kindern, Geschwistern, Freunden und Freundinnen in ständigem Verkehr. Ihre Briefe wurden von jedermann gern gelesen; denn sie waren einfach, gefühlswarm und innig.

Am 8. April 1923 Gg [Georg] Blaufuß[1]

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Familienarchiv Eckart, FA-S346 Chronik der Familie Eckart, zusammengestellt von Otto Eckart, Transkript.